Review of the Morakniv Garberg & Kansbol Survival Knives

by Jim Dickson

Sweden’s Morakniv factory has been making high-quality low-cost knives since 1891 and their Garberg and Kansbol knives reflect the Scandinavian attitude toward survival knives. The Scandinavian woodsman is also one of the world’s most expert axe men. Just watch a traditional Norwegian boatbuilder fashion a beautiful wooden boat with his axe. He doesn’t need a plane or the other woodworking tools associated with such work. He is the master of that axe, and it does everything he asks of it. Since an axe or at least a hatchet is going to be present the knife can be small. It will be used to make feather sticks for fire starting, preparing food, cleaning fish and game, cutting rope, and carving wooden tools.

Both the Kansbol Survival (S) and the Garberg Survival (S) have some significant advantages over the American Air Force Survival Knife which has a 1095 carbon steel blade with a leather handle and sheath. In a survival situation the blade can rust, and the leather can mold, mildew, and rot. The Garberg and the Kansbol have stainless steel blades and they have plastic handles and sheaths. Sweden’s answer to rust, mold, mildew, and rot in knives.

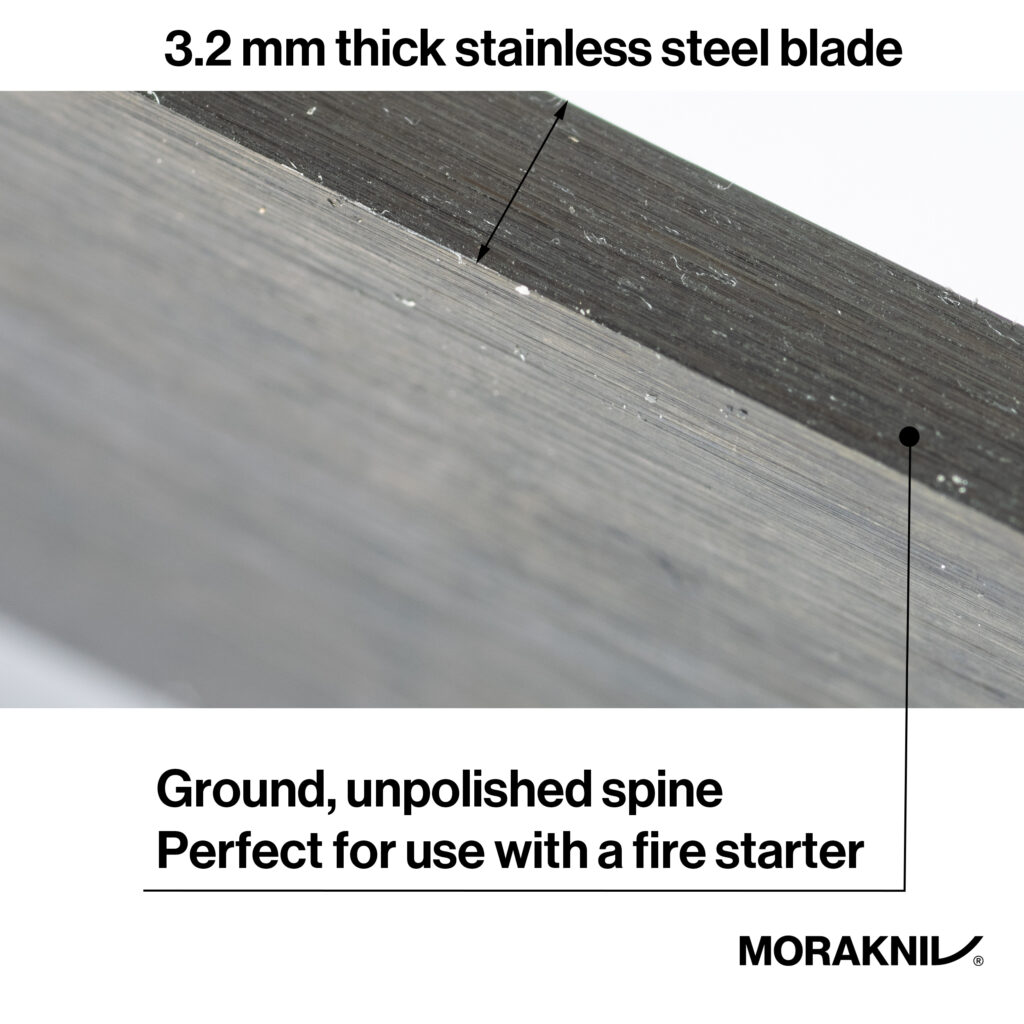

The American Air Force Survival Knife has a tiny coarse grit sharpening stone in a pouch on its sheath that is difficult to use effectively. The two Morakniv knives have effective diamond sharpeners plus a ferro fire starting rod attached to their sheaths along with a length of paracord. Their spines are sharp 90-degree angles so the back of the blades can be used to scrape sparks from the ferro rod or scrape tinder shavings off a piece of wood for the ferro rod’s sparks to ignite. I cannot emphasize too strongly how important these features can be in a bad survival situation.

Note that the Morakniv Survival Kit is also available separately so you can add it to your existing Kansbol or Garberg.

The American Air Force Survival Knife has a round cross section grip while the two Swedish knives have a flattened oval shaped grip that always lets you know where the cutting edge is positioned.

Both the Garberg and the Kansbol have 4.3-inch blades that are 15/16 inches wide at the widest point but the Kansbol’s blade is 2.5MM thick while the Garberg’s blade is 3.2MM thick. The Kansbol also has a special grind thinning the blade near the point for fine cutting that the more robust Garberg dispenses with.

The handles are identical comfortable, nonslip plastic handles but the Kansbol has the normal Morakniv tang that stops just short of going all the way through the handle while the Garberg has the tang going all the way out the back of the handle in the fashion popularized by the expensive Swedish Fallkniven knives. This makes the Garberg a tad longer at 9 inches overall compared to the Kansbol’s 8.9 inches.

The Garberg is also the heavier of the two weighing in at 13.8 ounces compared to the Kansbol’s 8.5 ounces. This difference is not enough for me to tell when I am wearing them.

Both knives are made as indestructible as possible with the heavier Garberg being the obvious winner in this department. The Garberg Survival is also available in a carbon steel version with a black blade.

Instead of a proper guard these two knives have a swelling at the end of the handle. This is partly because Scandinavians typically hold a knife firmly in the fist and rarely push towards the point. These handles are designed for comfortable use over long periods of time without causing the hand to cramp or get tired. This is a feature most Scandinavian customers insist on in their knives.

The Swedish 14C28N steel holds a good edge and has good strength and shock resistance. It has .62 carbon content and thus holds an edge noticeably better than the 420HC stainless steel found in most premium factory stainless steel knives which has only .45 carbon. Regular 420 steel is also used by some companies to make knives even though it has only .15 carbon! Not enough to matter. The Sandvik 14C28N steel holds a much better edge yet it is still able to be sharpened effectively in the field. This is critical for a survival knife. Never let a knife get dull out in the woods. Keep the edge always touched up just as a butcher or a chef does. You see them put the blade to a sharpening steel every time they pick it up before they start to cut.

A dull knife is unsafe as it takes too much force to make it cut and that force can cause it to get away from you and cause an accident. Also sharpening a dull knife can be a major project and not one best done out in the woods. When I hear stories of someone skinning umpteen deer without re-sharpening, I take it with a grain of salt, and I don’t know any bush dweller who wants to try such a stunt. If you want to go as long as possible without sharpening, then get a flint knife or a modern ceramic knife. They may be weak and brittle, but they hold an edge longer than steel does if that’s all you want.

Remember that a knife and an axe are not interchangeable. Use an axe for chopping and splitting wood and use a knife for cutting and carving. In a survival situation your life depends on your tools so you would be wise to baby them instead of seeing how much abuse that they can take. You just might find out.

One of the most important tools in a survival situation is a quarterstaff. This should be made of hickory or ash or yew if possible. The staff should be 6 to 9 feet long and 1 & 1/8” to 1 & 3/4” thick. If you are going to be walking on steep mountainsides the longer lengths are better. One end of the quarterstaff should be sharpened into a point and hardened in the fire for better use as a defensive weapon. The blunt end is the one in contact with the ground. The knife is the perfect tool for removing the bark and small branches and shaping the point. Traditionally a quarterstaff should be six inches taller than its user.

The quarterstaff is not only a weapon it is a means of preventing falls. Break a leg in the wilderness and you are reduced to crawling. It should always be used on steep slopes, boulder strewn areas, and when fording streams.

When building shelters, the axe cuts the poles, but the knife cuts the withies used to tie everything together. A withy is a flexible branch, ideally from a willow tree, that can be used to tie things with. You have to cut it off and also trim off the small shoots and leaves branching out from it.

A small knife is not a wood chopper, and I am very uncomfortable with the modern practice of people batoning a knife through a stick of wood they want to split. In this the knife is used like a shingle splitting froe. It is held over a stick of wood and then the back of the blade is struck with another piece of wood to drive it through until the wood splits. Well, I have two froes and they are heavy massive affairs, not thin knife blades.

As a blacksmith I have seen more tools broken under impact than under steady pressure and as a former Alaskan trapper I know just how brittle steel gets at 60 degrees below zero. You must warm your axe blade over a fire if you don’t want to risk breaking it at those temperatures. If you break your knife, you may not survive. Batoning may be something you can get away with but why would you want to take a chance on hurting your knife in a survival situation where breaking your knife could prove fatal for you? Leave wood splitting to the axe or hatchet and keep the knife for knife cutting jobs and you will stand a much better chance of surviving. An axe and a knife are very poor substitutes for each other. You need both if you intend to survive. I have also found a machete and a bolo knife to be indispensable at times. Everything has its place and a job it is best at.

Driving the point into a stick to form the knife into a drawknife may look like a good idea but that stick handle is not going to stay on and when it comes off you may get a serious cut that could impede your chances for survival.

Forcing the point deep into a log so you can cut against a stationary blade also may cause problems when the knife works loose. Anyone who has spent time with the Canadian Cree First Nation knows how safety conscious they are. There is a saying “White man cuts toward himself while the First Nation cuts away from himself.” The First Nations know that they can’t afford to be seriously hurt when they are back deep in the bush for the winter. Some of the tricks I see people do with knives are appalling to these woodsmen. Things like hammering a thin bladed Morakniv into a tree and using it for a step. What happens if the blade tears out of the tree or worse yet, breaks? Your whole weight is suddenly driving your leg past a broken blade with a razor edge. You can bleed to death deep in the woods from a wound like that. You don’t see Native Americans doing tricks like that just because someone got away with it.

One of the worst cases of using a knife for something it was not made for occurred in Alaska where a man was working inside a frozen moose carcass with a famous make lock blade folding knife. Now any old sourdough or Native American knows that a saw is the proper tool for this, but an axe can be made to work as well. This man’s only way to attack the frozen carcass with a knife was to stab at it like it was an ice pick. Bad idea. The locking mechanism of a lock blade folder is weak. Just put the blade in a vise and force down on the handle and it will give. Striking as hard as he could, the first time the point glanced off or it hit at the wrong angle the knife folded. Hard. It took off all his fingers. I never looked at folding knives the same way again after learning of his fate. It just goes to show what can happen when you use a tool improperly.

These two knives will do anything a knife this size is capable of. They are not a substitute for an axe, machete, or bolo knife any more than the aforementioned tools are substitutes for them. Anyone wanting a fine hunting and survival knife of this size will be well served by them.

About the Author

Jim Dickson has written for gun magazines in 13 countries since 1979.